The common comma: Part 1

First, let’s bust some...

Common comma myths

Myth: commas are hard to understand.

Truth: they’re really not.

Myth: you have to memorize an enormous list of rules.

Truth: you really don’t.

Myth: a comma is the same as taking a breath while speaking.

Truth: it’s really not.

Myth: marriages founder, friendships die, and professional relationships splinter over differences about whether or not to use a thing called “the Oxford comma.”

Truth: True. (OK, that’s a slight exaggeration! But read on...)

So why are commas often sticking-points? More to the point, why does that matter?

Commas do more than set off words, phrases, or clauses within a complete sentence. Commas actually form part of the message. With simple elegance, the slight pauses created by commas influence how readers interpret your writing. By separating written sentence elements in systematic ways, commas help readers better understand your meaning.

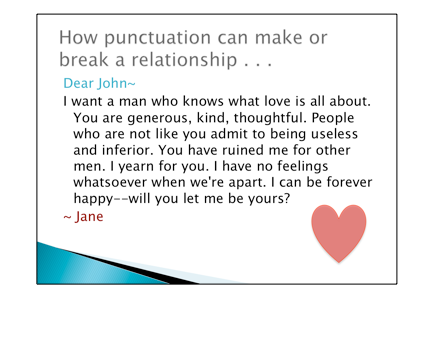

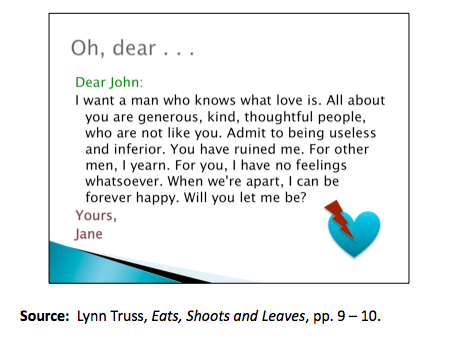

Check out this example:

Traditionally, a “Dear John” letter means bad news for a boyfriend or fiancé. In Lynn Truss’s bestselling book Eats, Shoots and Leaves, the only difference between these two versions is the use of commas and full stops (and one dash). This is a perfect example of how commas can shape meaning!

How punctuation can make or break a relationship (text version)

Absolutely necessary commas: Four basic patterns

Pattern 1: Before a coordinating conjunction when it joins two independent clauses. (Aren’t sure what those things are? See the blog post “Glossary of Grammar Terms.”)

Most of the superintendants gathered in the Great Hall, but the students snuck down to the dungeons.

Pattern 2: Before each coordinated word, phrase, or clause in a series or list.

Please be careful to pack the mushrooms, gooseberries, silverweed, and mint separately from the crushed manticore.

Pattern 3: After a word, phrase, or dependent clause that introduces an independent clause.

Single word: Indeed, the entire fifth-year class wanted the afternoon off.

Phrase: Holding his sword firmly, the White Knight faced the thin, shadowy figure of Lord Thorn.

Clause: When Esmeralda pushed the Evil One into an alternate universe, the entire realm celebrated.

Pattern 4: On each side of a modifying word, phrase, or clause that interrupts a sentence. Typical mid-sentence modifiers (“interruptors”) include

- conjunctive (connecting) adverbs such as “however,” “thus,” “similarly,” “therefore."

Professor Slitherfingers, however, decided not to attend the celebration.

Note: you can usually begin or end a sentence with a single-word adverb instead of using it as an interruptor. Your choice!

- appositional phrases. These often follow nouns, providing extra information.

Cookie, my best friend's irritating ferret, has been banished to the dog house.

- non-restrictive relative (who/which) clauses.

A powerful new troll-repelling spell, which for years remained locked in a secret vault, will soon be approved by the Chemistry Department.

A restrictive relative clause is essential to the meaning and structure of the sentence and does not take commas.

~~~~~~~~~

Get to know these four basic patterns, and you’ll (almost) always get commas right.

Ready to test your comma knowledge? Take the Recognizing Correct Commas Quiz!

Coming soon to Grammar Camp...when NOT to use commas. Stay tuned!

~~~~~~~~~