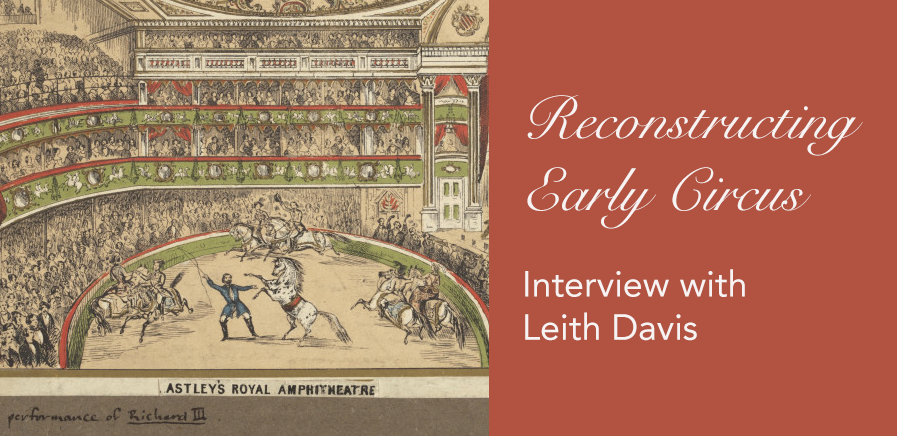

Reconstructing Early Circus: An interview with Leith Davis

Published by Alison Moore

This blog post was contributed by Sophia Han, a former Digital Fellow in the Digital Humanities Innovation Lab.

In this interview with DHIL, Professor Davis shares insights from working on the digital humanities research project.

The archive’s website describes the performances of Astley’s as “a public space which ‘remixed’ the latest novelties and current events with a variety of physical entertainment.” How does the idea of “remixing,” help us to understand what early circus looked like?

Early circus developed in a layered kind of way. The form we now know as circus can be traced back to the performances of Phillip Astley and his wife, Patty, in London in the late 1760’s. Astley had served in Colonel Eliott's 15th Light Dragoons during the Seven Years’ War in Europe, distinguishing himself for his horsemanship skills. He returned to England and, with Patty, set up a riding school at Ha’Penny Hatch in Lambeth where they also performed equestrian tricks. There had been trick riding before that point of course, but the Astleys’ innovation was to perform equestrian feats in a circle, a ring, and to have people pay to enter the premises and watch them perform. Phillip Astley was an entrepreneur and had the idea of tapping into novelty in order to get people to come back again and again — he and Patty did different tricks, they teamed up with a bee-trainer and groups of acrobats, they included songs and dancing in the performances. The circus also grew to include pantomime performances, theatrical spectacles with music, elaborate sets and transformations. Astley’s Amphitheatre also included reenactments of world events — the storming of the Bastille and the death of Captain Cook in the Pacific, for example. So in this context, remixing means that the Astleys brought together all these novel elements and newsworthy moments into this remixed presentation, creating a mobile and fluid performance. As theatre, circus had a tremendous impact. People loved it, and it was available to all classes as it offered tickets ranging from very cheap to expensive. Other circuses sprang up in London and abroad. There was even a circus in Montreal in the 1790s. This was a global movement.

How did the project come about?

I had a SSHRC grant to conduct research on early circus in the British Library in summer, 2017. I worked there with my former graduate student, Emma Pink. To our surprise, we found a collection of three volumes of newspaper advertisements about Astley’s. It took a solid week of clicking with our phones and cameras, but eventually we took pictures of everything so we would have the data we needed when we returned.

What research question did you have in mind when you started the project?

I knew the project was about circus, that it involved trying to find out about traces of the performances, but I had no idea what I’d find as data. Michael Joyce (from DHIL) created a database to help record the data. But when we found the three volumes of advertisements,we modified the database accordingly just to focus on those items. It was definitely an organic process.

There are choices in all archives. There are decisions to collect certain things and not to collect other things.

How did the digital archive influence your research?

The database offers new ways of understanding the resource of the newspaper advertisements. You can read through them to see how the circus has developed over time. Or you can search and find out when particular acts were performed or when particular acrobats were featured. You can ask new questions about these performances. With this database, you can look at everything in different contexts. Some of the interesting aspects of research that the database has offered for me personally have been a glimpse into the world of female circus performances as well as the circulation of acts and performances between the circus and the other theatrical venues in London at the time. Eventually, I’d like to expand the archive to include the performances at other circuses and see how acts were performed in certain locations. For instance, one really interesting aspect is racial representation in England versus the U.S.

When you started your research, did you have a digital humanities project in mind?

I had been skeptical about DH because much of the research I had read seemed to draw conclusions that didn’t look all that different from the sort of conclusions you’d find using close textual analysis. Later, I got to know more about DH and to read more sophisticated uses of the methodologies, but had never embarked on a project myself. Now I’ve become familiar with the fact that DH projects allow one to ask different questions for research.

As a public archive, the project is accessible to a general audience. Did you have a non-academic audience in mind when you started the project?

I had been asked to join Song & the City, a symposium organized at King’s College, London in October, 2017. So that was what initially got me going on the project. The audience for my research was originally academic. But as I worked on it, I realized that the topic has a fascinating appeal for people who are non-specialists, too — people who are interested in entertainment and circus, and British history. The DH database is an accessible way to share research. I also hope to use the database for undergraduate and graduate classes which would incorporate research into circus and also involve learning some circus skills. For the website itself, looking into the future, I would love to develop it so that users could create their own virtual circus acts, somewhat like a video game: Build your own circus.

What do you think is the role of digital archives in preserving documentation on historical moments?

There are choices in all archives. There are decisions to collect certain things and not to collect other things. James Winston back in the 19th century collected newspaper clippings about Astley’s with the idea of writing a book on theatre and circus. He had in mind what he wanted to collect and preserve. There are also decisions and choices in the curation of DH projects. With the archive, I’ve amplified what Winston started but I’ve made this collection more accessible and enabled more people to learn about Astley’s and early circus. Otherwise, the materials would have languished in the British Library. Actually, at one point, on a later visit to the British Library, when I requested the materials, I was told that the library no longer had them. They were eventually found, but it brought home to me how ephemeral the collection actually is.

My next project is a digital project involving an 18th-century Jacobite manuscript (The Lyon in Mourning), a hand-written collection of materials concerning the Jacobites after their defeat in Britain in 1745. With the help of the National Library of Scotland and the DHIL, I’m now bringing it to light. Digital archives make different parts of history more visible.

Often, it’s media that don’t circulate widely that show us a different perspective on history.

What is it important to make this work visible?

The stories contained in The Lyon in Mourning represent the stories of people who were not the victors of the historic Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. The creator of the manuscript, Robert Forbes, was arrested when he set out to join Bonnie Prince Charlie. He was put in Stirling Gaol, then Edinburgh Castle, and he wrote down the stories of his fellow prisoners as a memorial. He wrote them by hand, and his work would eventually grow to 10 volumes. The Lyon in Mourning is also a relic, as Forbes pasted pieces of cloth from clothes that Bonnie Prince Charlie wore onto the covers of several volumes. With the DH project on the Lyon in Mourning, we’re bringing to light this earlier conflict, as well as providing the perspective of those who lost. The project also shows us the relationship between media and history. As a work of manuscript (and a politically dangerous object at that), the Lyon in Mourning was not disseminated. Instead, the perspective that was circulated widely in print was that of the government forces. Often, it’s media that don’t circulate widely that show us a different perspective on history.

Professor Davis’ project on The Lyon in Mourning is currently in development with DHIL. More information about Reconstructing Early Circus: Entertainments at Astley’s Amphitheatre, 1768-1833 can be explored in the British Library’s Digital Scholarship blog, an article for the Romantic National Song Network and a scholarly article: "Between Archive and Repertoire: Astley’s Amphitheatre, Early Circus, and Romantic-Era Song Culture," Studies in Romanticism 58.4 (2019), 451-480.