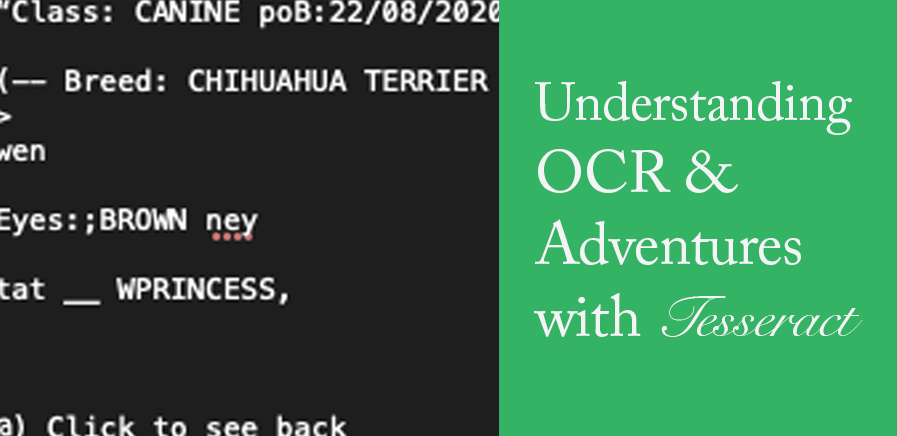

Understanding OCR and Adventures with Tesseract

Published by Alison Moore

An OCR Workflow Primer for Beginners

If you’re working with print materials such as newsletters, scrapbooks, zines, handwritten documents or even marginalia, you may be considering the use of some basic computational methods to support your textual analysis. In this case, you’ll likely need to figure out a digitization process and identify the software and tools that will work best for you and the research you’re undertaking.

With the ubiquity of document scanning devices (even your mobile phone can act as a scanner!) and software like Adobe Acrobat, digitization of texts may seem like a straightforward process, but options for converting scanned images into a format that’s machine-readable vary.

In this post, I discuss my experience learning how to install and use Tesseract, an open source software for optical character recognition (OCR). It may help to understand that digitization is the process of scanning or capturing features of your source materials and converting them into digital images, while the process of making the textual contents of this image “readable” to a computer requires the use of optical character recognition (OCR) software. Your choice of software can depend on the size of your document sample, the type of analysis you’re hoping to do, costs, and the workflow complexity you’re willing to deal with.

One free and relatively-accessible option is the open source software, Tesseract. It’s available for both Linux and Mac OS, but the Homebrew package installer makes it easy to set up on Mac devices. Installing both Homebrew and Tesseract requires use of the command line via the Mac Terminal app, and while many instructions for installing Tesseract assume at least some experience with the command line, this article by Grace Nolan is a short read for absolute novices.

Because Tesseract is open source, it has a strong online community and there’s a plethora of documentation available on the web. An accessible resource with basic command line examples is available on the Illinois Library website while the New York University library has a guide for more advanced commands.

What does Tesseract do?

Once you’ve installed Tesseract, you can use the command line to process images (normally saved as TIFF or jpg files) into .txt files but also PDF and PDF-related formats. While Tesseract does more than just “read” texts from image files, its strength is in batch processing and extracting text from a large sets of files, which can then be used for various purposes and leveraged by additional programming languages like Python or Ruby. In this sense, it’s a very scalable resource because even though it’s useful for complex tasks, it can also be used for digitizing smaller collections.

Caveats

Tesseract has several drawbacks:

- While it can “read” handwritten block letters, it cannot read cursive handwriting.

- You need to download and install the correct language to read the images correctly.

- Images must be of good quality.

- It will read lines of texts from left to right but may have trouble reading lines of texts layed out in columns unless you “train” it to do so.

Some of these issues can be addressed by preparing your files as much as possible. For instance, you can use ImageMagick with Tesseract to reduce visual “noise” – those speckles and marks that can be picked up and digitized during the scanning process. This NYU resource suggests a number of workarounds using ImageMagick. The latest version of Tesseract can also be “trained” to read certain inputs correctly as this case study shows.

Even though the learning curve of Tesseract is steeper compared to a paid OCR conversion tool like ABBYY Reader, its flexibility and relative ease-of-use makes it a useful resource to explore.

For my part, I decided to install and experiment with Tesseract because I wanted to understand what the OCR process entails in a way that I couldn't learn from clicking on a button in an all -in-one cloud platform like ABBYY FineReader.

My Experience with Tesseract

So first, it may help to know what knowledge I had before installing Tesseract. As someone who teaches visual communication and Adobe CC software, I’m familiar with different graphic formats and have an inkling of what the command line is – at least enough to switch directories, locate files and install the occasional script.

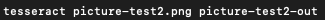

As mentioned, there are many online resources to help with the installation process but I found it surprisingly difficult to find a simple example of a command line instruction to actually run the program. On a Mac with a Homebrew install, you would type the following on the command line:

Typing “tesseract” runs the program on the file “picture-test2.png” and “picture-test2-out” is the name of the .txt file which the program outputs. Some things I learned from troubleshooting:

- Be sure to run the command from the directory (file location) where the graphic files are saved

- If you’re telling Terminal to run Tesseract on a file with an extension, be sure that this extension is included in the file name.

- Don’t add layers to redact content using Preview or Paint, as Tesseract can detect the edges of these layers, interpreting them as “diacritics.” When I flattened the layers in Photoshop, Tesseract did not interpret these layers as diacritics.

- While 300 DPI for TIFFs are generally recommended in forums, lower resolutions for PNG files seemed to work fine. “Cleanliness” seemed to be determined by the amount of contrast between pixels defining the outline of the characters and the background.

Example outputs

The first image I tested was my dog’s custom identification tag. I thought this would be interesting to try as it looks somewhat official and has the sort of watermarks typically seen in government documents.

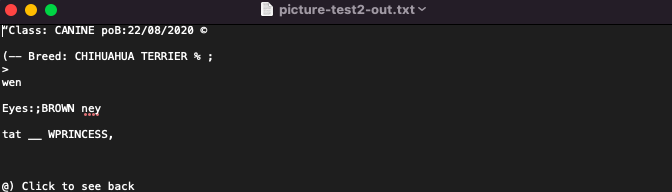

What did Tesseract output?

You can see that Tesseract is best able to extract characters without a background and cannot read handwritten text or cursive fonts. Since tesseract has not been specifically trained to parse this kind of image, it cannot tell the difference between the text characters and the graphical shapes in the coloured/textured background, interpreting every mark it sees as possible text to read. With the right library and dataset, you can “teach” Tesseract to interpret marks as intended but that is far beyond my capability.

So while the above image didn’t produce a great result, the following did produce the results I was hoping for.

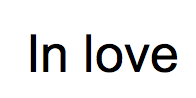

This is a screenshot of the words, “In love” typed out in Photoshop and saved as a PNG. Tesseract was able to recognize and interpret the letter shapes like this

Excellent. So this second example gave me a better idea of what Tesseract could do well. One thing to note here is that since Tesseract is trained to recognize specific languages, it can determine that, in this context, it is most likely that the first character is a capital “I” (and not a lowercase “L”).

What I learned

Now of course these examples represent extremes among the kinds of documents you potentially scan for textual analysis. For myself, as someone who might be interested in scanning zines or community newsletters made using collage techniques, Tesseract wouldn’t be an ideal option. Instead, I’d probably think along the lines of uploading a PDF version of the zine and then manually adding notes or commentary as metadata.

However, this experiment did teach me to think more about the processes involved in digitization and how the choice of OCR tool might depend on the sort of analysis I’m considering, as well as the PDF format I might consider uploading to a public database. For anyone analyzing text from fairly “clean” scans of documents with simple page layouts, Tesseract is an ideal choice, especially for a researcher wanting to learn more about how or why we make “texts” digital for analysis in the first place.

Further Reading

Homebrew

Terminal for beginners

5 Reasons why Researchers Should Love the Command Line

Illinois Library Introduction to OCR

Tesseract OCR Software Tutorial from New York University Library

Tesseract Documentation