This handout describes the six elements of a well-reasoned argument and explains how they all work together. Created by philosopher and educator Stephen Toulmin, this framework helps writers build arguments that sceptical readers will consider reasonable—even if they don’t agree!

Claim

A claim is a debatable statement that requires proof. You may find it useful to distinguish among 3 types of claims: fact (It will rain today.); judgement or evaluation (System A is superior to System B for watering crops in rotation); and policy (All farmers in our valley should use System A instead of System B). Keep in mind that a claim is only the starting-point for a fully developed argument.

Reason

A reason is a statement justifying the claim (e.g. a “because”-clause). A reason then invites EVIDENCE (sometimes called DATA) to support a claim and show its validity. For example--"You don’t have to water the tomatoes [CLAIM] because it will rain soon” [REASON]. How do you know that? “My smart phone weather app predicts rain will start around noon” [EVIDENCE]. But will your audience believe the evidence? That might depend on the reliability of your smart phone app, or whether whomever you're trying to convince is willing to accept that your smart phone app is reliable. If your audience accepts the evidence, they will see your claim as valid.

Qualifier

A qualifier is a word or phrase (adjective or adverb) that limits the scope or generalizability of your claim. Without a qualifier, your claim may seem too broad or unrealistic for your readers. For example, if you say--"Students struggle with writing"--you would be making an overstatement or overgeneralization: it's simply not true that "all" students struggle with writing. So a more reasonable claim, a claim for which you're likely to find supporting evidence, would be--"Many students struggle with writing." Using qualifiers appropriately also helps you to avoid binary or “either/or” thinking, which can invalidate an argument. For example—

[[topright start left half]]

Try...

- sometimes, at times, occasionally, frequently

- many, some, more (or if applicable, a precise number or amount)

- a few, a small number, most (or if applicable, a precise number or amount)

- probably, possibly, likely

Instead of...

- always / never

- all (or assuming “all” is understood)

- none, no

- totally, absolutely

Warrant

A warrant is an assumption or point of agreement shared by the arguer and the audience. In argument, we rely frequently on these fundamental shared assumptions. Warrants may remain unspoken (“understood”) when a writer and reader can be expected to know or agree on them. Whether spoken or not, the warrant provides a vital link between the evidence and the claim. But if readers don’t share the same assumptions about the validity of the writer’s evidence, or if they don’t recognize the assumption, they may not accept the evidence or claim.

Backing

Backing is additional information that justifies or enhances the credibility of your evidence. How do you know your audience will accept your data or evidence? You may need BACKING. For instance, if you give evidence like—"My weather app predicts rain will start around noon"—you may need to add, "This is a good app; more than 90% of users gave it 5 stars." For this backing to work, you and your audience must share an understanding about what 5-star reviews mean for apps (e.g. qualities like reliability, ease of use, etc). This understanding would be a WARRANT.

Conditions of rebuttal

Conditions of rebuttal are the potential objections to an argument. To deal with possible objections, imagine a sceptical yet reasonable reader poking holes in your claim and reasons or coming up with opposite, equally valid reasons. To deal with such objections, you may need to provide additional evidence, add a qualifier, express a warrant, or change your warrant. "Though not all readers will accept these . . . they will at least see that you haven’t ignored their point of view. You gain credibility and authority by anticipating a reasonable objection.” [Lunsford, A. A. and Ruszkiewicz, J. J. (1999). Everything’s an argument. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s, p. 93.]

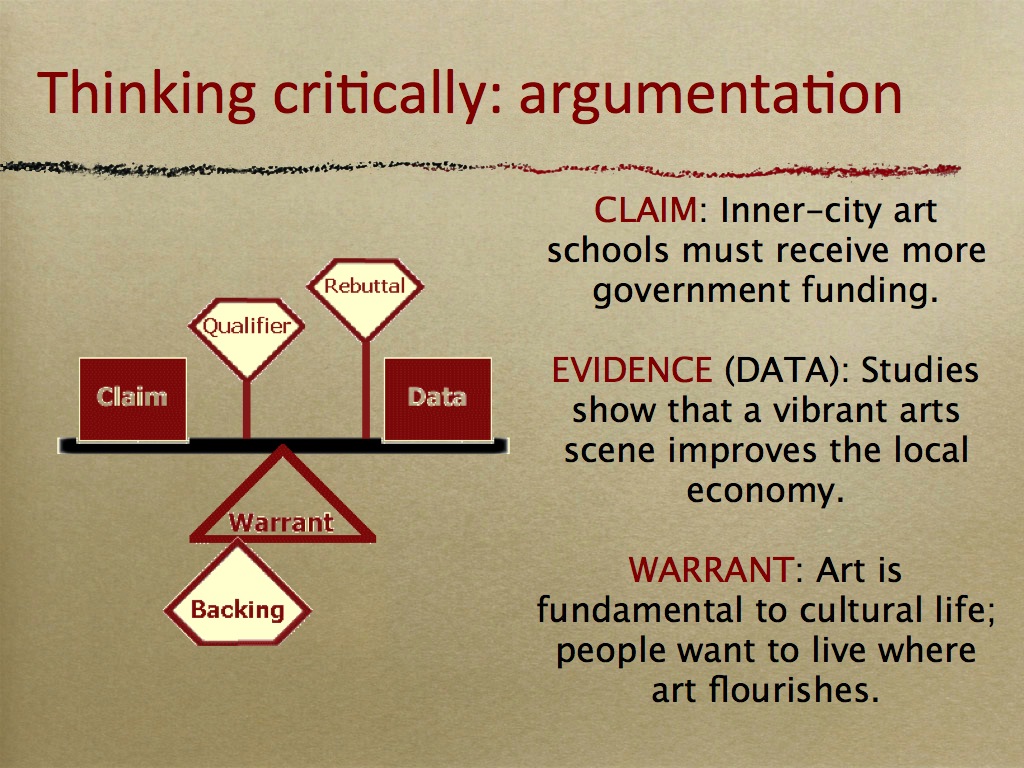

Finally, this diagram may help you visualize how all the elements in Toulmin's model work together:

Image credit: http://owlet.letu.edu/contenthtml/research/toulmin.html