What is a literature review, and why do one?

Literature reviews summarize the existing conversation on a topic. They can accomplish something similar to environmental scans, researching industry best practices, summarizing evidence-based approaches, or laying the groundwork for a new initiative. A literature review can be done as its own complete product, or it can serve as an introduction for the original research you plan to do to add to the conversation in your field. In academic research contexts, such as for theses and dissertations, they provide a grounding for the new work a scholar is presenting to add to this conversation.

However, most guidance available on conducting literature reviews does not consider how to do a literature review in a nonprofit context, or outside of university settings in general.

What a literature review could do for you

Outside of academia, your motivations for research may be different. For a non-profit, literature reviews might help you:

- Gather evidence to assess your organization’s best practices

- Provide evidence for grant proposals

- Look for new approaches to an issue

- Provide background or a methodology for your original research

- Synthesize what’s known on a topic, to share with others working in your area

- Find out if someone has already studied the topic you are interested in

What are the steps?

What you're looking to create may not be exactly a formal literature review. Most guidance on conducting literature reviews assumes an academic context, with strict guidelines for how a review should be conducted. As a non-profit or NGO worker your resources, needs, and audience may be different from researchers in academic institutions.

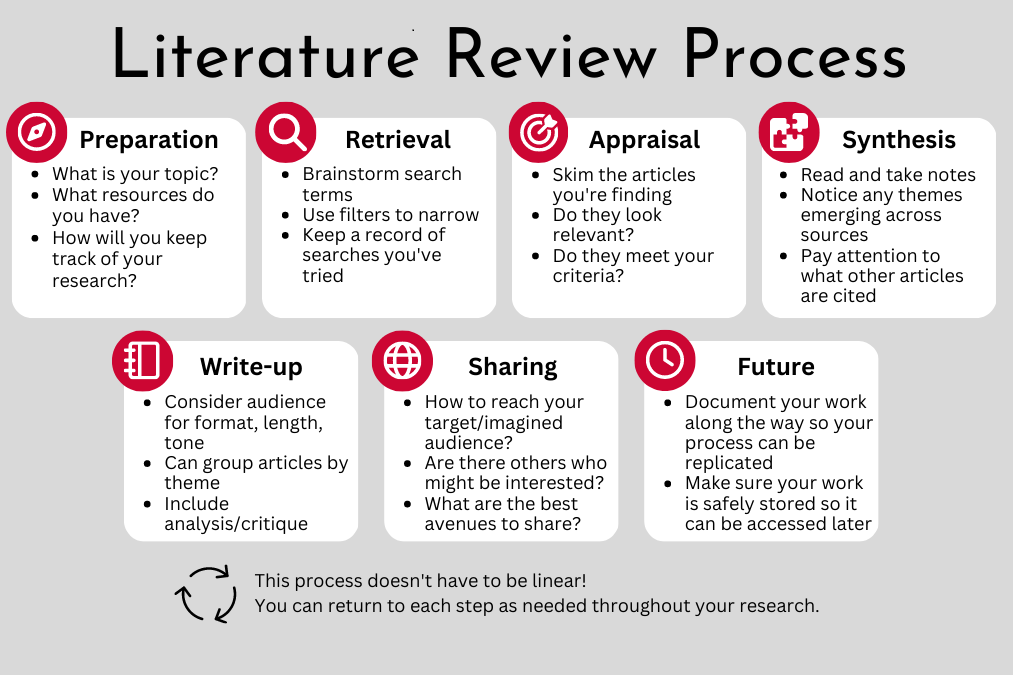

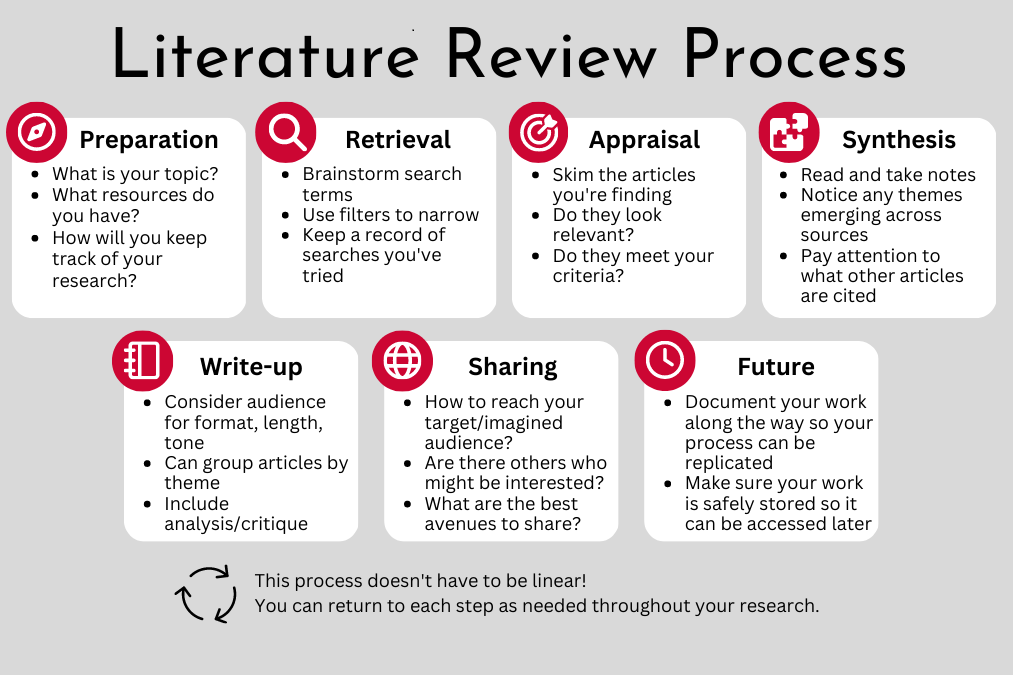

Here is a structure to follow based on the literature review process, with questions to consider along the way to help you tailor the process to your context. Each step is described in greater detail below the infographic.

Preparation

Think through your needs, capacity, and resources to plan your work.

What is your topic?

What is your motivation for creating a review on your topic?

Do any literature reviews exist on this topic already?

What resources do you have?

People:

- Do you have fellow staff or volunteers that could contribute to this project?

- How much time do you (and others) have to dedicate?

- Do any staff or volunteers have relevant experience to contribute?

Information and supports:

- You may have more resources available to you than you realize.

- See "Where to search" in the "Retrieval" section for more ideas.

How will you keep track of your research?

Keeping track of sources:

- To keep track of the sources you intend to use, you can keep a list in your own document, or you may want to consider using citation management software.

- Citation managers are designed to make it quick and easy to track and cite your sources. You can read more at Citation management software and tools.

Keeping track of the information you're collecting:

- What kind of note-taking works well for you?

- Even if something feels memorable in the moment, it can be difficult to remember where you found a piece of information even the next day.

- Many citation management tools allow you to add notes or attach documents.

Retrieval

Brainstorm search terms

Consider any possible search terms that relate to your topic -- it's useful to try different combinations of words to see what results you get back. Your early searches may help you find relevant terms to add to your list.

Use filters to narrow

You can also consider what kinds of articles will be relevant to your needs, then use search filters to narrow your results to fit those criteria. For example, if you are looking for recent articles, some databases give you the option to filter by publication date.

Keep a record of searches you've tried

It's a good idea to keep a record of your searches: a list of what keywords or filters you've used, on what website, and what you were able to find with each search. This can help you locate sources again later, and have a record of what has worked well so you don't repeat work.

Resource links: The collapsed "Where to search section" below describes some options of where you may be able to find information and documents, as well as support services that could help you in your research. "Research strategies" contains more information on research strategies and approaches.

Where to search

Open web (search engines like Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo):

- Tools for searching for Open Access articles (CORE plug-in, OA button)

- Advanced Google search tips

- Grey literature search tips - grey literature is information produced outside of traditional publishing and distribution channels - things like newsletters, working papers, speeches, reports, and policy literature. It often comes from NGOs, government, industry, and other organizations.

Potentially useful collections:

- SFU list of Open Access databases

- Directory of Open Access Journals

- Academic library databases -- use Open Access filters in search (SFU guide, UBC guide)

- Open content on JSTOR -- a digital library of academic journals, books, and primary sources in the humanities and social sciences

- Downtown Eastside Research Access Portal -- contains research and related materials relevant to Vancouver's Downtown Eastside

- Cochrane Library -- a collection of databases with evidence to inform healthcare decision-making, including systematic reviews, controlled trials, etc. (not all Open Access content, but many articles are)

- Candid. Issue Lab -- an online collection of free research, evaluations, case studies, toolkits, etc.

- Frontier Life -- a digital collection of primary source documents relating to colonialism in North America, Australia, Asia, and Africa

Paid databases:

There are a few other resources that may assist you in your search or provide you access to additional materials. For example, public libraries may subscribe to databases that would then be free to patrons to access. Academic libraries also sometimes allow guests to visit in person and use university computers to access their electronic resources like databases. Other options include:

- Paid searching services (InfoAction at the Vancouver Public Library, for example)

- Access you may have as a member of a professional organization (eg. Electronic Health Library of BC member organizations)

- Professional organizations you are a member of may also have their own independent library collections

- Databases that have free registration that allows limited access

- JSTOR free account - a digital library of academic journals, books, and primary sources in the humanities and social sciences

- You may qualify for the Community Scholars Program

Research strategies

Appraisal

Skim the results you're getting: do they look relevant? Do they meet your criteria?

Screen the results you're getting: are they relevant to the topic you've chosen? Do they fit the criteria you've selected for retrieval? You don't need to read the full article at this stage -- you can read the abstract or skim headings. If the article looks relevant, save the full text to read once you reach the synthesis stage.

Resource links

Evaluating sources:

- Evaluating Sources - from the University of the Fraser Valley on scholarly vs. popular sources, news sources, images, and the "filter bubble"

- Evaluating Information Sources - from the University of British Columbia on evaluation frameworks and checklists

- CASP Checklists - checklists for evaluating methodology and study design

Choosing relevant sources for your topic:

Synthesis

Read and take notes

You’ll be doing a lot of reading, so keep notes on each source you find. This can be done in the notes section of your citation manager, or your own document.

Pay attention to which other articles are cited

The other articles your sources are citing can clue you into other important research in the field -- especially if they appear in multiple of your sources.

Notice any themes emerging across sources

Recognizing patterns or themes (i.e. in findings, specific aspects of your topic studied, methods of research, conclusions) will be useful when you begin your write-up to help you link articles together or contrast them.

Resource links

Write-up

Consider audience for format, length and tone

The form of your finished product may differ based on your audience, needs, and purpose. Should the write-up be thorough or brief? Casual or formal tone? Purely text, or with visuals?

Structure: can group articles by theme, include analysis/critique

Generally, a literature review should contain:

- An introduction -- where you explain why you've conducted this research, your context, and give readers a preview what you'll discuss and how that will be structured

- Body paragraphs -- these can be organized by theme, comparing and connecting related articles

- You don't need to fully summarize each article, and you also don't need to include every article on a topic -- just what's relevant to you!

- Element of analysis/critique -- consider which sources you find particularly useful, and the positives or flaws they may have

- Conclusion -- how does it all add together? Does anything seem to be missing from the scholarship as a whole? Did you learn anything that's useful to your organization and its practices?

There are many possibilities to shape the format to your needs. Your literature review could contain an executive summary to explain your project and call out key findings. It could end with recommendations for action in your organization and beyond. It could take the form of an interactive web page. It could have bulleted summaries, photographs, and graphs.

See below in the "Examples" section to see some possible structures that incorporate some of these elements.

Resource links

- Academic writing: What is a literature review? - guide from the SFU Student Learning Commons on what should be included in a literature review and how to organize it

- Literature Reviews - guide from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill on writing a literature review. "Strategies for writing the literature review" and "Begin composing" sections may be most helpful in how to create your write-up

Sharing

How to reach your target/imagined audience?

Revisit: who was your original target or imagined audience?

Are there others who might be interested?

Now that you've conducted your research, are there any other groups (whether internal or external to your organization) who would be interested in what you've created? These could be community members, local leaders, professional organizations, or partner organizations you work closely with.

What are the best avenues to share?

What methods are available to reach your target audience and other potential groups you've identified? Trade publications, blogs, email lists, or conferences might be good places to share your work. Internally, newsletters, meetings, and emails could be effective.

Planning for your project's future

Document your work along the way so your process can be replicated

Keeping notes on your process (searches, sources, etc.) throughout your research allows you or others in your organization to pick your work back up later, or to replicate your process on a different topic.

Make sure your work is safely stored so it can be accessed later

Ensure your notes are kept somewhere secure and reliable, where others in your organization can also access it as needed.

Examples

The following links contain literature reviews conducted by and for community groups and nonprofits. They provide an example of the different forms your literature review could take.

Further resources

For more detailed advice on literature reviews, see our guide on literature reviews for graduate students.

For more information on citation, see this page on citation and style guides, this guide on citing Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers (APA 7), and this piece on citational justice by Neha Kumar and Naveena Karusala.

Acknowledgments

This guide draws on research supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. It was developed as part of the Supporting Transparent and open Research Engagement & Exchange (STOREE) research project.

Thank you to the Community Scholars and others who reviewed drafts of this page, including Savannah Swann from the Dr. Peter Centre.