The Indigenous Curriculum Resource Centre (ICRC) in the W.A.C. Bennett Library is here to support faculty members, instructors, and course designers to decolonize or Indigenize their courses, with a collection that focuses on:

- impacts of colonization on Indigenous Peoples in Canada;

- what decolonization means in different subject areas;

- importance of authentically including Indigenous scholarship and voice in course materials.

The ICRC collection is built on the ARC definition of “Indigenization” as uplifting Indigenous knowledges and weaving or braiding them into current pedagogy and curriculum, to be learned alongside Western knowledges. Responding to Call to Action 21 from the Aboriginal Reconciliation Council’s (ARC) final report, Walk this path with us, the ICRC aims to help faculty learn how and why to do this work in a good way.

On February 07, 2023 the Indigenous Curriculum Resource Centre was the site of a Cedar Brushing Ceremony by Səl̓ílwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish) community members, organized by Chris Lewis (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh) and Angela George (Sḵwxwú7mesh). During this ceremony, drummers accompanied cedar brushers as they cleansed the space, furniture, and materials. This work was undertaken to prepare the space, furniture, and materials for their new purpose; to support decolonizing and Indigenizing pedagogy and curriculum.

ICRC space and design elements

Located on the 4th floor of the W.A.C. Bennett library, the ICRC looks north towards Səl̓ílwətaɬ and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw. The location of the space holds significance that wasn’t consciously considered during the planning process. The number four is important for many Indigenous communities as it represents the four cardinal directions.

It’s also the space where many books catalogued into the E78-99 range were shelved; for those unfamiliar with Library of Congress Classification (LC), that call number range is used for "History of the Americas: Indians of North America." This call number range is problematic because most, if not all, books about Indigenous topics and communities are located here regardless of whether they are about history. An example of this misclassification into E78-99 is Sara Florence Davidson’s (Haida) book, Potlatch as Pedagogy: Learning through Ceremony. According to the official cataloguing metadata, this book should have the call number E99 H2 D285 2018, with E99 being the call number for "History of the Americas: Indians of North America: Indian tribes and cultures." Yet the book is about pedagogy, the theory and practice of learning. Beyond placing the book in such an inappropriate location, the LC system uses outdated and harmful terminology. We’ll come back to cataloguing later, but for now let’s go back to the space.

There are low bookcases with cedar plank surrounds along three sides of the ICRC. The cedar tree, known as x̱ápay̓ay in Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim or χpey̓əɬp in hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, is an important medicine for many Indigenous communities. With the bookcases being surrounded by cedar planks, the books shelved there are being cradled by a strong medicine. In addition to its use as a medicine, cedar is used in everyday and ceremonial practices in Indigenous communities. From clothing and baskets to canoes and houses the cedar tree was and continues to be important to Coast Salish communities. The bookshelf surrounds are horizontal planks, like how the walls of a Longhouse or Big House are built.

To provide unobstructed views of the land, and to bring the landscape into the Library in honour of Indigenous knowledges, we have removed the heat registers and kept the window nooks clear of furniture.

In the space are two couches, two styles of chairs, stools, and two sizes of tables. Connie Watts, Nuu-chah-nulth, Gitxsan, and Kwakwaka'wakw, worked with Jenna Walsh, Natalie Gick, and me (Ashley Edwards) on selecting furniture options and colours. It was important to have seating that was comfortable and could be moved so people have the option to gather around a table. The couches were chosen to reflect how water and wind are often depicted in art. The colour represents the waterways that provide both transportation and sustenance for local First Nations and urban Indigenous peoples.

With the lack of walls, artwork was a bit of a challenge but something we all wanted to include. Indigenous communities record stories, laws, and histories in what is currently recognized as artwork, and this form of literature has traditionally been excluded from library collections. I selected seven Susan Point (Musqueam) prints from her Circles in Time series from SFU Galleries and hung them on the seven pillars between the windows in the space. Seven is also an important number for Indigenous communities, and our responsibilities are often talked about as extending seven generations forward and back. Having seven pillars and seven prints felt, to me, like Creator was watching over this project. Across from the ICRC, on a wall shared with the computer lab in room 4009, are four more prints from SFU Galleries. These are by artists Maynard Johnny Jr., Dylan Thomas, and lessLIE.

On the east and west sides of the space, above the bookshelves, four weavings will be hung in the second half of 2023. These weavings were commissioned from Debra Sparrow (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm), Angela George (Sḵwxwú7mesh and səlilwətaɬ), Chief Janice George and Buddy Joseph (Sḵwxwú7mesh), and Atheana Picha (q̓wa:ńƛəń), in collaboration with SFU Galleries.

ICRC Collection

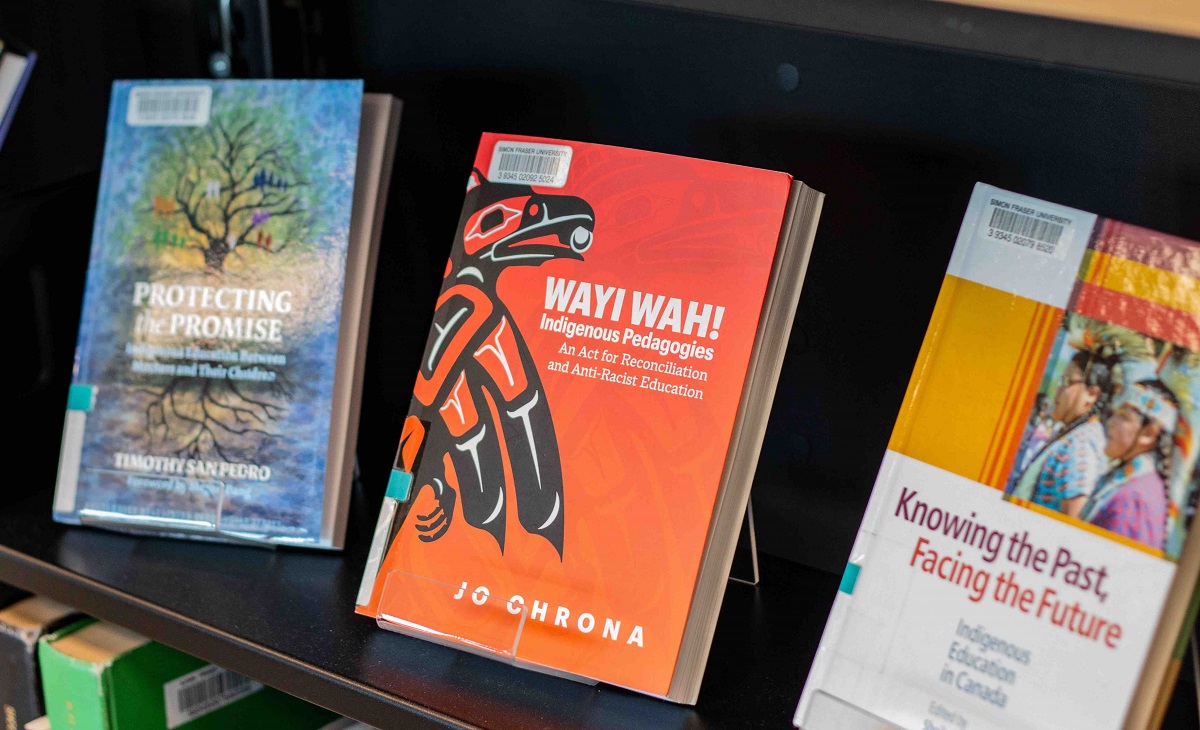

The ICRC Collection supports the decolonization and Indigenization of curriculum, pedagogy, and classroom practices; a need for this collection was expressed in the final report of SFU’s Aboriginal Reconciliation Council, Walk This Path With Us. It’s a broad collection, with items supporting all areas of study at SFU, but with a narrow focus on curriculum and pedagogy. Because of that, the collection doesn’t include all scholarship and publications written by or about Indigenous peoples. You will find very few fiction items or personal narratives in the ICRC for example.

Instead, the collection includes books on topics like Indigenous pedagogy, Indigenous Research Methodologies, and the decolonization of specific subjects (e.g., education, political science, etc.). There are some books that address assimilative educational practices forced on Indigenous peoples (I.e., Residential Schools, Boarding schools, etc.), because we need to know the history of education in this country called Canada. We need to know what has happened, so we don’t forget, and learn from it. These texts can support better understanding of the need for decolonization and Indigenization, but the ICRC also firmly advocates that these colonial practices are not and should not be mistaken for “Indigenous education.”

Instead of using the standard library classification system, the Library of Congress Classification, the ICRC collection uses a locally modified Brian Deer Classification system. The system was designed to honour relational ways of understanding the world, which is foundational to Indigenous knowledges. The books are shelved east to west, to symbolize a new day and new beginnings. The collection itself is an act of decolonizing library practices.

Media centre

Facing the windows is a media centre where visitors can engage with the audio-visual content that is part of the ICRC collection. An example of this is the Salish Weave Box Set: Art and Storytelling Project, where Coast Salish artists share their influences, processes, what it’s like being a First Nations artist, and how art is a source of knowledge sharing. These conversations are a way to bring orality into the collection, as well as expand the traditional concepts of literacy and literature.

People are invited to sit in the ICRC and look out over Səl̓ílwətaɬ and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw while they listen to Coast Salish artists.

ICRC Classification system

When developing the ICRC, Indigenous perspectives and ways of understanding were a core part of the process. This understanding also informs how the books are classified and catalogued; that is, how the books are organized and arranged on the shelves.

Traditionally, academic libraries use the Library of Congress Classification (LC) system, which was developed in the late 1800s for the collection which became the presidential collection in the USA. As mentioned above, this system places nearly all Indigenous topics, scholarship, and voices in the History section. Why? Well, at the time there was an assumption that Indigenous peoples would either die out through the genocidal tactics engaged by the governments, the diseases brought over by settlers, or that we would all assimilate into the “body politic” (to quote Duncan Campbell Scott), that is, give up our Indigenous identities and cultures. This didn’t happen, and our communities are still here today and thriving. Yet, library classification systems have resisted updating to reflect the living reality of Indigenous peoples and knowledges.

The ICRC collection is catalogued using a locally modified Brian Deer Classification system. The Deer is an Indigenous classification system developed in the 1970’s by Mohawk librarian Brian Deer. It was written honouring Indigenous ways of understanding the world, specifically relationality. It was also designed to be flexible for the collection, by having the collection itself contribute to the main and subheadings. This flexibility allows libraries and cultural institutions to modify the framework to support the purpose of their collections.

With call numbers, the next alphanumeric set is what we call a Cutter in library jargon. They generally represent titles, names, and places, and contribute to the organization of books on the shelf. The SFU Library cataloguing team came up with a Cutter system for the ICRC Classification that ensures the relationality of items can be honoured. A Cutter number is created based on the B, C, and D sections of the ICRC Classification system (these sections are "Indigenous Communities") and are separated from the call number by a backslash; e.g., An item about Skwxwú7mesh would have the cutter “\BFQ”. A Nation or community Cutter will be included when an item is specific to them, and on works of fiction, drama, and poetry, etc. to indicate an author’s Nation or community.

For Potlatch as Pedagogy, the Cutter \BL (for Haida) is used after JF. This way, any other books about Haida pedagogy and pedagogy grounded in Haida knowledge or ways or knowing will be shelved together. In LC, the first cutter would often be the author’s last name. While important, this system would see the Haida community’s knowledge scattered throughout the "Indigenous education philosophy and theory, general" section, and only books written by the same author grouped together. This Cutter system means that Haida knowledge (as related to educational philosophy) is together, and next to nearby communities. The full call number for Potlatch as Pedagogy is: JF \BL D28 2018.

Using an Indigenous way to arrange materials is a decolonial change to knowledge organization, and something only a few academic libraries are doing. LC invalidates and erases Indigenous communities and knowledges. The ICRC respects and uplifts them.

What this all means

The Indigenous Curriculum Resource Centre was envisioned to support those in teaching and course design positions at SFU learn why and how to decolonize their pedagogy and practices. Through this learning people will be able to respectfully begin incorporating Indigenous scholarship and voices into their classrooms and work. While developing the ICRC, I was able to also work towards decolonizing library practices. While not a part of the original call to action, these changes to library practices have become an exciting part of the ICRC initiative, and other post-secondary institutions have reached out to learn from our work and about the modified Brian Deer System.

The library profession and practices have their roots in European library traditions, and understandings of literacy and literature. Through the space, art, and classification system, the ICRC is pushing back on those understandings and offering another way to view knowledge – one that has always been here.

Please contact lib-indigenous@sfu.ca with any questions.

Ashley Edwards, May 2023.