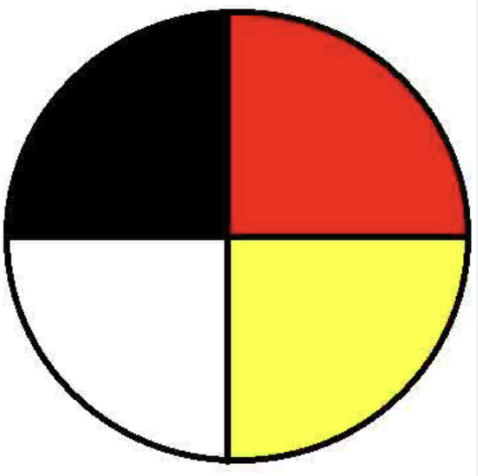

Project 57 Week 54: Medicine Wheels

Many will recognize this image as the Medicine Wheel. Despite the familiarity of this image for many, it is more accurate to speak about Medicine Wheels (plural), as there are many culturally specific iterations of this imagery and associated sacred teachings (Joseph, Indigenous Corporate Training Inc, 2025).

Bob Joseph (Kwakwaka'wakw) writes that the term “Medicine Wheel” itself comes from the Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming, which is the largest wheel in North America, but has been applied more broadly to this imagery by non-Indigenous people. Joseph explains that the original name is “sacred circles” and that this name applies to ancient stone circles that are found throughout North America, the oldest of which dates to 4,000 BC (Joseph, Indigenous Corporate Training Inc, 2025).

As ancient symbols, Medicine Wheels or scared circles are used to “represent the interconnectivity of all aspects of one’s being” (Bakes, n.d.) and “the four stages of life and the four winds [...] the continuous cycle and relationship of the seen and unseen, the physical and spiritual, birth and death, and the daily sunrise and sunset” (Beaulieu, 2018). Medicine Wheel symbolism is present in many First Nations and Métis communities, however the knowledge and teachings contained within these sacred circles differs across cultures (Beaulieu, 2018). Furthermore, not all First Nations, Inuit, and Métis cultures or peoples use medicine wheel symbolism (Bakes, n.d.).

In their cultural contexts, Medicine Wheels are forms of knowledge documentation and support powerful intergenerational teachings. Savannah Bakes’ (Ermineskin Cree Nation) curriculum documentation outlines ways to connect Medicine Wheel teachings to the grades 9-12 BC Curriculum in the areas of science, physical education, art studio, outdoor education, and BC First Peoples. In the book The 7 Lessons of the Medicine Wheel Kelly Beaulieu (Ojibway) organized lessons into the following focus areas: The Four Directions, the Four Seasons, the Four Elements, Animals, Plants, Heavenly Bodies, Stages of Life (Beaulieu, 2018).

Medicine Wheels are a compelling and rich source of cultural knowledge and teachings. However, sometimes, the medicine wheel imagery is used in ways that promote a pan-Indigenous understanding. Chelsea Vowel (Métis) post on her blog about Pan-Indianism/Pan-Métisism even refers to the Medicine Wheel as an example. She writes,

"I am particularly conflicted when it comes to the Medicine Wheel. This is a Plains symbol, and from what I understand there are different teachings associated with it, depending on which Plains culture you come from [....] I think it is a good metaphor for holistic approaches to healing, learning, governance and what have you…but the Medicine Wheel as most of us know it today is anything but traditional. It is new, and it is Pan-Indian.

[....] I don’t want to be told that this is a part of our tradition as though all natives have some cosmic link to this teaching. I don’t want people who are struggling to reconnect with their communities to be fed a culture that isn’t theirs. It devalues and obscures our own traditions and the worst part of it, in my opinion, is that we are complicit in this. We write ‘Medicine Wheel teachings’ into our curriculum, into our health strategies, into our visions of governance and so on." (Vowel, 2011).

We quote from Vowel at length here because she is pointing to the problems with using any imagery in a pan-Indigenous way: this is a misappropriation of culturally specific knowledge, symbolism, and teachings and it can lead to cultural confusion and dilution.

Vowel writes “the Medicine Wheel as most of us know it today is anything but traditional. It is new, and it is Pan-Indian" (Vowel, 2011). The opening to Bakes’ curriculum document reads, “teachers should understand the medicine wheel is a sacred and ancient symbol” (The Medicine Wheel). These two points are not as contradictory as they may seem upon first reading. The knowledge and teachings that accompany sacred circle imagery are, indeed, ancient, and derive from “thousands of years [that Indigenous Peoples have spent] connecting with the land, following traditional protocols, and taking part in ceremonies to harvest these medicines and understand their purpose” (Bonneau, 2020). Vowel’s point, however, is that the iconography of the Medicine Wheel has become a part of popular culture – very often in ways that are divorced from the original cultures, Elders, and Knowledge Keepers who are able to provide appropriate context and understanding of their significance. Through this process, contemporary engagements with Medicine Wheel symbolism and teachings, though perhaps rooted in ancient and sacred knowledge, become something new, as Vowel has argued. Indeed, this process can be seen by the very fact that these images are known as “Medicine Wheels” and not as “sacred circles” or by terms in the many Indigenous languages where these teachings originate.

In sum, Medicine Wheel imagery and teachings originate in distinct First Nations communities and are unique to them. Using a generic Medicine Wheel image or metaphor as a shorthand way to designate a project as having Indigenous content is a misappropriation of this culturally specific imagery. Such a misappropriate is disrespectful and can undermine the integrity of a project or idea. It is therefore important to ensure that you understand the context, nuance, and cultural specificity of any imagery, including Medicine Wheel imagery, before making use of it in your research, writing, reports, or projects (Biin, Canada, Chenoweth, Neel, 2021).