On this page

This guide is meant to provide a brief introduction to literature reviews for students in the applied sciences. Each subject area within the applied sciences has its own additional conventions and protocols, so you should consult other more detailed resources in addition to this guide, as well as your subject liaison librarian.

Literature reviews are just one of the many types of reviews that exist. For example, systematic reviews in the health sciences typically have specific criteria based on their particular subject area in medicine. If your research has more in common with the social and behavioral sciences, consider our guide for literature reviews in those areas. Also, we have other guides on finding literature reviews and writing literature reviews as well.

Why a literature review?

All research has a context within its academic discipline. New discoveries and results are a response to gaps in existing knowledge, and add to the current state of what is known about any given subject area. A literature review provides readers with this context and shows how the new work fits into the existing conversation within the specialized subject area.

In their book Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review, Booth, Papaioannou, and Sutton describe carrying out a research project without doing a literature review to be like visiting a new and interesting country but never leaving your hotel room: when you return home you would not be able to describe the new country to your friends (p. 1).

More precisely, a scientific literature review assembles and summarizes the research in a particular subject area, and describes its evolution to the present state of what is known. Doing a literature review at the start of your research project will help you to familiarize yourself with your subject area and understand it more thoroughly. In addition, such a review will show other researchers that you know and understand your subject area well.

Typically you would not include every single piece of related research, but focus instead on the research that is accepted within the discipline as being important in that subject area. If you are unsure of what to include, consult faculty and graduate mentors or peers to get their assessment.

Your literature review should lead the reader to open questions and new directions of research that naturally arise from a discussion of previous work. This will show how the gap in what is currently known can be addressed by your new research, and places your new discoveries in a context.

Searching the literature

When looking for relevant sources for your review, there can be several ingredients in your search:

- using publications by important authors and researchers in the subject area;

- finding books and articles by moving from keywords to subject headings in your research area;

- finding important results in the subject area (these can be found using what is called 'citation mapping' or 'citation indexing');

- browsing important journals in the subject area (using citation counts, and via the Journal Citation Reports® or the SCImago Journal Rank from the Scopus® database); and

- talking to your faculty advisors, and to mentors and colleagues.

More details on some of these approaches are in this and further sections below.

Try to identify the main studies and texts in your research area since they will typically cite the most important research results and journal articles in the field. For example, you could start with graduate textbooks and subject-specific encyclopedias since they include bibliographies. Also, most graduate theses and dissertations include a literature review of their research area that you could use as a starting point. Theses and dissertations written at SFU are all collected in our repository Summit, organized by department and subject area.

Review articles are also a good source for subject-specific bibliographies; when looking for journal articles, start with a broad search so that you don’t miss research that may be useful. Browsing some article abstracts will give you ideas for more specific search keywords, and will also give you a sense of prominent authors and researchers. Then narrow your search using filters for subject areas, dates, review articles, and so on. For example, in the Web of Science database, you can search by topic keywords and then filter your search results under “Document Types” by restricting to “Review” on the menu on the left. You can also search for the topic and include the term “literature review”as an initial search keyword, but this may miss some useful results. More suggestions on finding relevant journal articles are in the next two sections below.

Depending on your research area, consider different kinds of sources for your literature review: books or ebooks, journal articles, conference papers, technical reports, theses and dissertations, standards, patents, and so on. Also, where possible, it is always best to find the original source of an idea that you plan to include in your review.

What about using Google Scholar? As with any resource, it has both benefits and drawbacks, and so it is important to be aware of the pros and cons of using Google Scholar.

Keywords or subject headings?

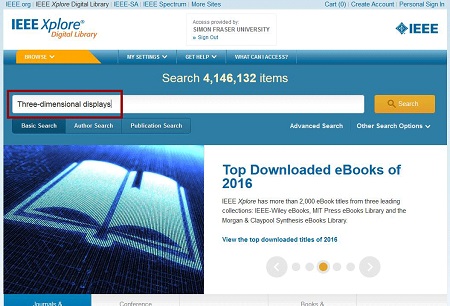

Start with keywords that describe the main concepts in your subject area. Once you have search results, identify relevant sources and move to subject headings by using the specific terms that have been associated to the source. Here is an example of how this could work in the IEEE Xplore database:

1. First, search with keywords.

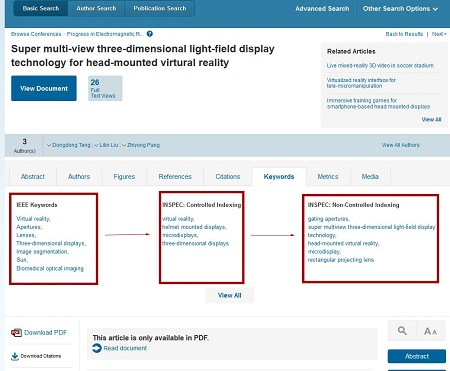

2. Find an interesting article from the search results.

![At page for an article ("Super multi-view three-dimensional light-field display technology for head-mounted virtural [sic] reality"), Keywords tab option is highlighted](/system/files/31977/keywords-tab-450w.jpg)

3. Browse through subject headings assigned to the article to find other similar articles; in IEEE Xplore, the subject headings are called "IEEE Keywords".

This constant adjusting of your search terms by moving from keywords to subject headings is sometimes called "cycling your search", and helps improve and fine-tune your search method. Every database should have subject headings, but the actual subject heading terms could vary in different databases.

Once you find a relevant source that has useful articles listed in the bibliography, you can find the full-text article from a citation on the SFU library homepage.

Important authors, articles or journals

Citation mapping or citation indexing can be used to find important results in your subject area. Basically, the method uses the scholarly practice of citation to do two things: find links between different articles (both going forward and backward in publishing history), and rank articles in terms of importance.

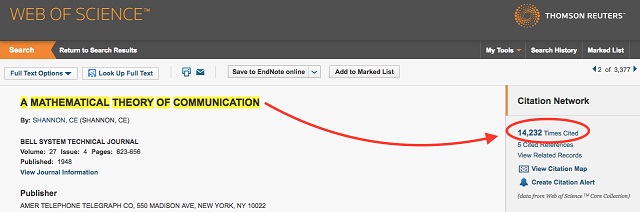

If you have found an important journal article in your subject area, then you can easily see what has been cited in that article by simply looking at it's list of references at the end. But in many cases you can also look forward, to find more recent articles that have cited your original important article. The Web of Science database is one way to look forward; let's see how this works with Claude E. Shannon's important article A Mathematical Theory Of Communication, published in 1948. On the article result page in Web of Science, the menu on the right shows a 'Citation Network'. This links citations both forward and backward, and also allows you to get alerts whenever a new article is published that has cited Shannon's original paper.

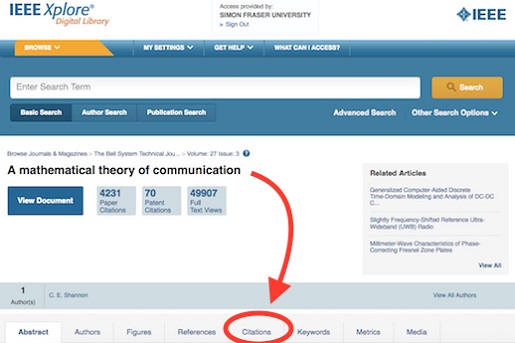

We can also see this citation information in the IEEE Xplore database -- on the article page for the same paper, A Mathematical Theory Of Communication, a tab for 'Citations' contains links to articles that have cited Shannon's original paper.

Google Scholar also provides this kind of citation indexing, but it is generally not as reliable as the previous two systems.

Notice the large difference between the number of citations this very important paper has received: 4231 in IEEE Xplore vs. 14,232 in Web of Science (both numbers as of April, 2017). These discrepancies are due to the different sets of journals and publications that each database is using to count citations. The Xplore number is mainly using other IEEE publications only, while Web of Science is using results from their many different subject databases across several publishers. Either way, it's a really large number of citations!

What if you don't have an important paper to begin with? You can still use databases like IEEE Xplore or the Web of Science to identify important results in your subject area, by finding articles that are cited most often. In both databases, you can do keyword or subject heading searches and then sort your search results by the number of times cited. Here you are using the idea that more important results and papers tend to be cited more often.

In your search for relevant articles, it makes sense to be current by looking for recently published work; but don’t ignore older papers that could be “classics” in your field.

Finally, you could browse important journals in your chosen subject area. Journals are commonly ranked in terms of research impact, and via the Journal Citation Reports® or the SCImago Journal Rank from the Scopus® database you can identify the top ranked journals in different subject categories. Remember that such ranking systems often change, and that they may use algorithms or ranking methodologies that are not actually valid in your discipline. Don't use journal ranking systems as a substitute for talking to your faculty mentors and colleagues!

Document your search & manage citations

Write a short summary and take notes on each paper you read as you go through it. This will help you remember which ideas appeared in each paper, and you can also use this writing in your literature review later on.

Also, once you have a useful search string (with the precise keywords or subject headings combined together) make sure to record this so that you can reproduce the search consistently across different databases.

Keep up-to-date with research in your area by saving your searches in any given database, which can either be re-used or used to send you search alerts by email. For example, IEEE Xplore, Web of Science, ACM Digital Library, Google Scholar, and others provide this feature. Most involve the creation of a free account with their service, which is separate from SFU Library.

Are you finding a very large number of possibly relevant articles and other sources? The best way to avoid information overload and getting swamped is to be organized! For example, consider using a citation management tool that can manage your papers and citations. Most citation management tools allow you to add notes to each paper, and to add your own customized keywords, which you can then search later on. Make sure you compare citation management systems before deciding on the best one for you.

Useful links

- SFU Library guide to literature reviews for graduate students

- Research Commons at SFU Library offers writing services and graduate writing resources

- Online Handbook: Components of Documents: Literature Reviews (2016) from the Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering at the University of Toronto

- Engineering Literature Review from the Kelvin Smith Library at Case Western Reserve Library